10.12.2020

Preventive restructuring of companies in 2021: possible course of procedures under the draft German Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act and the impact these procedures will have on the real estate market

The German legislator is planning to further develop German restructuring and insolvency law. The core element will be the introduction of a new business stabilisation and restructuring act. This law is intended to provide companies with a set of instruments allowing them to restructure outside of insolvency proceedings and to discharge their debt. Should the law come into force at the turn of the year as planned, it will also have an impact on the real estate sector.

The draft bill for an “Act on the Further Development of Restructuring and Insolvency Law” (“SanInsFoG”) contains a package of changes and innovations in the areas of restructuring and insolvency law. It primarily serves to transpose the EU Restructuring Directive into German law. For this purpose, the German legislator is planning to introduce a new “Act on the Stabilisation and Restructuring Framework for Businesses” (“StaRUG”, hereinafter: “Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act”), which is intended to come into force as early as 1 January 2021.

The Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act will provide the procedural basis for the implementation of business restructuring procedures outside of insolvency proceedings. The successful implementation of restructuring plans outside of insolvency proceedings has so far required that consensual agreements aimed at restructuring be reached with all the affected creditors. Where such agreements cannot be reached, the only option left is for the company willing to restructure to start insolvency proceedings with the strict procedure-bound restructuring options that they offer. The Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act now opens up a middle way for companies: if a relevant majority of creditors agree to the restructuring plan that has been prepared by the company, and this plan is confirmed by the competent court, the restructuring of the company can succeed even against resistance from individual creditors and without conducting insolvency proceedings.

To secure their continued existence, companies can use a variety of restructuring and stabilisation instruments that the Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act will make available to them, like a toolkit. There is, therefore, no “one” procedure that always follows the same pattern. Instead, a company that wishes to restructure can choose which of the tools made available by the Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act are most suitable in the relevant case and will, therefore, be used. With the involvement of the restructuring court, a stay of execution or realisation can be ordered, for example, or mutual contracts that have not yet been fully performed can be terminated. However, the tools of the preventive restructuring framework under the Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act are only available to companies that are not yet insolvent. If a company is already insolvent, i.e., if it can no longer meet its payment obligations that are due, the only option that remains is to initiate insolvency proceedings.

The central element of any preventive restructuring under the Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act is the restructuring plan. Its structure is comparable to that of an insolvency plan: the restructuring plan, too, contains a description of the background and basis of the restructuring and of the effects that the restructuring will have on the creditors’ claims and, as part of a restructuring concept, defines the positions of those of the creditors who are included in the plan.

The restructuring plan is drawn up by the company itself and is then discussed and agreed with the affected creditors, who, divided into groups of creditors, must decide on the plan. In principle, each group of creditors must approve the plan with a majority of 75% of the voting rights in order for the plan to be adopted. In order to protect creditors, the Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act partly contains special rules on the formation of groups of creditors and on majority decisions across groups (“cross-class cram down”). The restructuring plan can be decided upon in a private autonomous vote and the decision then be confirmed by the competent court; alternatively, the vote can take place immediately within the framework of court proceedings. If the restructuring plan is approved with the required majority and this is confirmed by the court, the plan will take effect also in relation to those affected parties who had voted against the plan or wo did not participate in the vote.

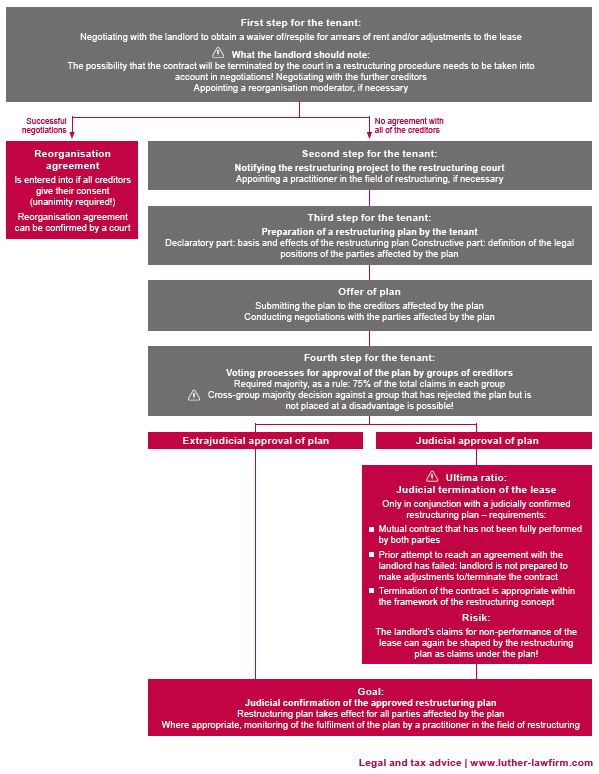

The following case study provides an example of the course a restructuring procedure could take for a company that is in arrears with rental payments as a tenant of commercial space and is threatened with insolvency. In this scenario, the tenant would be likely to take the following steps towards the goal of successful restructuring:

This example shows that the landlord’s rights can be significantly affected by the tenant’s restructuring procedure. However, the procedure also offers the landlord the opportunity to actively participate in shaping the restructuring, and to get involved in the negotiations and voting. In this context, the landlord, as the tenant’s creditor, should always consider how the effects that the restructuring plan could have on its claims as landlord compare to classic insolvency proceedings.

In particular, the landlord should take into account that the tenant can obtain a termination of the lease through the court as a last resort. The possibility to terminate the contract is a powerful tool which is being given to the company that is willing to restructure by the Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act. After the early termination of the lease, the landlord would only be left with a claim for non-performance of the lease against the tenant. However, even this claim could still be “shaped” within the framework of the restructuring plan. The economic consequences of the termination of a contract can, therefore, be quite significant. This undoubtedly strengthens the tenant’s negotiating position. Yet, as the termination of the lease would have to be integrated into a comprehensive restructuring plan, the tenant would have to approach the landlord in order not to jeopardise the success of the restructuring of the tenant’s business. Finally, in most cases both the tenant and the landlord will have an interest in continuing a long-term tenancy.

If the Business Stabilisation and Restructuring Act comes into force as planned, the tools of the preventive restructuring framework will offer companies the opportunity to restructure outside of insolvency, and without the “stigma of insolvency”. As shown in our case study, the creditor contributions required for this can be economically significant. This is why we recommend that not only those companies wishing to restructure, but also the creditors that would be affected in the particular case take a closer look at the new, planned set of rules and the associated options for action to optimise their legal position.

And last but not least, a practical tip: in cases where a tenant falls into arrears and fails to pay the rent for one or more months, landlords tend to apply any rent received later (possibly after a reminder and threat of legal action) towards the amount of rent that has been outstanding the longest. However, this could be a problem in the event that the tenant subsequently becomes insolvent.

Example: the tenant does not pay the rent for the months of August, September and October. After a reminder and threat of termination, one full month’s rent is paid and received in mid-November. If no provisions are made or in place regarding how to apply this payment, the landlord uses this incoming payment as the rent for the month of August; the rent for September, October and November remains outstanding. The payment received in December is then used as the rent for September and so on.

In July of the next year, the tenant files for insolvency. The insolvency administrator will (successfully) contest all payments of rent made since November; as a result, the landlord will suffer a “loss” in an amount equal to the rent for 11 months. In contrast, if the landlord had applied the rent received in November towards the amount of rent owed for November, the rent received in December towards the rent for December and so on, the landlord could object to the insolvency administrator’s right to contest with some prospect of success that the relevant transactions were “similar to a cash transaction”. The landlord’s loss would then be limited to the outstanding rent for August to October, i.e. three months’ rent.

Therefore, from a landlord’s perspective, care should be taken to always apply incoming rent payments first towards the month in which the payment is received and only thereafter towards older claims.

Nicole Bittlingmayer

Partner

Frankfurt a.M.

nicole.bittlingmayer@luther-lawfirm.com

+49 69 27229 24710

Ruth-Maria Thomsen

Partner

Frankfurt a.M.

ruth-maria.thomsen@luther-lawfirm.com

+49 69 27229 24677

Matthias Wagner

Partner

Frankfurt a.M.

matthias.wagner@luther-lawfirm.com

+49 69 27229 18835